August 25, 2019

In the South Pacific, our American accents make it obvious that we’re foreigners, and many people we meet in the process of day-to-day living (waitstaff, store clerks, Uber drivers, etc.) ask where we’re from and how long we’ll be visiting. It’s the question of “how long we’re visiting” that sparks a discussion about our lifestyle, which includes explaining that we’re living on a boat and sailing the world. We talk about cruising and it being a lifestyle choice (often for older retired people but there are plenty of young people out here, too), and about making the twice-yearly migration between the tropics and New Zealand or Australia.

Some people know exactly what we’re talking about and say, “Wow, you’re living the dream!” Most people have never heard of doing such a thing and are full of questions, asking if we’re expert sailors, extremely brave, get seasick, have children, if we’re ever scared, encounter pirates, and the consistent one, “Have we been in any big storms?” (I’ve been meaning to write a post answering all these questions and will do so in the future).

This scenario hasn’t changed at all here in Kona, Hawaii, one of the state’s biggest tourist meccas. We use Uber all the time and are frequently asked where we’re from and how long we’ll be visiting (Uber drivers are often friendly people who are genuinely interested). And so we end up telling our saga and get the usual questions.

We don’t mind answering questions, and in fact, it’s rewarding to open the eyes of younger people to a possibility for their future that’s never occurred to them. I make it my business to present this life choice honestly and fairly and encourage people that they, too, can do this someday if they have the desire, aptitude and constitution for it. The good thing about talking to younger people is this possible future often depends on choices they make as they go through life. (Older people are often so embedded in their lives that it would be very difficult to change course unless this is something they’ve already been thinking about.)

Something that brought this topic to mind came from seeing my doctor in Los Angeles. He asked about the danger of pirates, and I tried to explain that pirates are not an issue in the area of the south pacific between New Zealand/Australia and the island groups of Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu and New Caledonia, nor are they an issue in the cruise from Los Angeles through French Polynesia and across to Tonga. Pirates just aren’t there.

Pirates are definitely a concern off the coasts of Venezuela, Somalia, and maybe some parts of Indonesia (although I’m not sure that last one’s still an issue), but not where we’ve been. In fact, I reminded him that he’s much more likely get car-jacked (road pirates) or have an accident on he way to work than we are to encounter pirates. He brushed this off as a non issue as that’s a risk everyone’s used to, still insistently sticking with his worry about pirates.

He’s not the first person to overestimate certain dangers we face while cruising. A while ago, I was talking to a person who was horrified that anyone would bring their children cruising, comparing it to child endangerment or abuse. I asked her if she ever drives her children in a car and pointed out the risks of an automobile accident are higher, in the extreme, to anything that might happen to a child on a cruising yacht. She said well yes, but we’re used to that.

Used to that? It seems a common response when I point out how much more dangerous it is to ride in a car, especially at high speeds, than it is to cruise on a yacht. Being “used to” something doesn’t make it any less dangerous. Being used to driving risks in particular does not make the twisting metal, flying glass, or the force of a high-speed impact any less destructive to the human body. Anyone employed in the medical, law enforcement, paramedic, or morgue professions can attest to that. Then there are the many devastating injuries that can happen to those who survive.

In the United States, 37,000 people die in road crashes each year, over 1,600 of them children under the age of 15. All of these people were used to the risk, but that didn’t help them when the inevitable came along. (I say inevitable because the average motorist will be in approximately four accidents in their lifetime—it’s luck of the draw as to how bad it is.) Frankly, I think putting a child on the boat is saving them from the dreadful risk of riding in a car.

Even with the major risks of cruising: hitting a reef, failure of the rig, and catastrophic failure or weather that leads to having to abandon the boat, the likelihood of death for a child is tiny, I think because people with children are a little more careful about the conditions they choose to head out in. Yea, dad might be a hard-core racing sailor, but if he wants to head out in harsh conditions, he’ll generally have his family fly in to meet the boat or wait for a gentler time. He knows that while he may survive the ocean, his partner may kill him or make him wish he were dead.

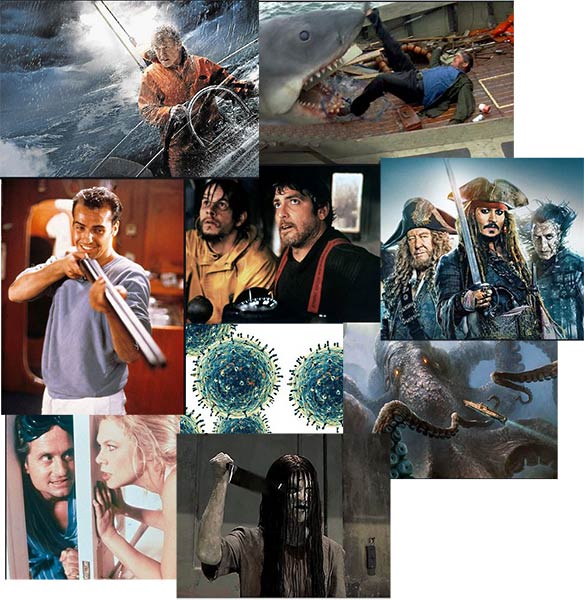

Setting aside the perceived dangers of violent storms or roving pirates-like those exasperating French New Caledonian pirates trying to pilfer our Starbucks coffee and Kraft Mac n Cheese because they’re so overcome with jealousy-there are some true dangers we face out here, I think often underestimated by the cruising community. These dangers include other boaters, sharks, heat, disease, getting drunk, and a few other miscellaneous issues.

I’ve already talked about the dangers presented by the wind and sea in my most recent post (or more specifically, making the deliberate decision to head out in risky conditions), and I’ll share my thoughts about the others in a series of upcoming posts.

Until then… Cyndi

Note from Rich:

When people ask: “When you get in a storm, aren’t you afraid you’re going to die?”

Me: “No, but I’m often afraid I’m not going to die!”