October 17, 2019

Human beings are highly affected by group behavior, which becomes most apparent during any given cruiser migration season (May/June and October/November are the peak times for making the big passage between New Zealand and the tropics) but can happen any time cruisers are waiting to make a passage that involves any sort of difficulty.

What often happens is when one boat makes the decision to head off, other boats just assume that person has some superior knowledge, or that there’s a magical power and safety in numbers. Thus when we ask someone about a questionable decision they’re making, we often hear, “There’s another boat going,” as though that’s justification for the rightness of the choice. This brings to mind my mother asking, “If your friends jump off a bridge, would you?”

The extreme end of this scenario happens when there’s a group of boats waiting for a weather window to make a big passage. One boat decides to go, then another, and then more boats proceed to jump on the bandwagon at a rapidly increasing rate that can border on a frenzy. Frankly, this scenario reminds us of a herd of buffalo—one starts to run and soon they’re all running, even if it means running over the edge of a cliff. The more people who are heading off, the more “right” the decision seems to those still wavering, and joining the growing group feels like the safest thing to do.

One problem here is that while the decision to leave might be right for the boats who initially make the decision to head out, it’s often not a good decision for many of the joiners. People lose sight of the fact that boat speeds vary greatly, and larger boats and catamarans can outrun weather systems that smaller boats cannot. Less obvious but a huge difference is any given boat’s engine power and speed.

I tell the story below not as an example of the Sheep Mentality but as an illustration of how “safety in numbers” is often an illusion, one that can get people into trouble. This happened to us in 2016, and it’s a lesson I haven’t forgotten because the outcome was so surprising to me.

We had set out from Napier (a city on New Zealand’s north island) for the Marlborough Sounds on the South Island, a trip which would include crossing the notorious Cook Strait between the two islands. This trip would take us about 30-some-odd hours, requiring an overnight trip. If everything went as planned, we’d start out motoring in light air, get some wind during the night to help us along, make a turn west under the North Island, and cross the cook strait to arrive in the Sounds before dark the following evening, about which time the wind was due to pick up.

We headed out on a beautiful sunny and calm day, making our way out of Napier’s harbor before heading south. About a half hour or so after we left, we were surprised to see another sailboat appear behind us. We hailed them and they, too, had left Napier and were headed for the Sounds. We were both motoring down the coast, but they were much closer to shore which seemed to be giving them an advantage as far as current. It was also apparent they had a powerful engine, surprising in that their boat wasn’t much bigger than ours.

They were making such good time under power that it wasn’t long before they passed inside of us and ended up in the lead, then out of sight completely and out of radio contact. They were so far ahead of us that they had much stronger winds during the night than we did, and they continued to pull further ahead. By the following evening they had rounded the bottom of the North Island, crossed the Cook Strait, made it in through the Tory Channel (the closest entrance into the Marlborough Sounds), and were anchored in a peaceful bay by nightfall.

Meanwhile, having fallen far behind, we hit a counter current which slowed us down even more as we neared the south tip of the North Island. We don’t have a big engine so this cost us a fair amount of time. The wind was picking up as predicted, and we realized that our weather window was closing and we wouldn’t make it across the Cook Strait that night. Instead, we decided to head for the city of Wellington, on the south side of the North Island, and had to do some beating as we headed into that harbor. Since we’d expected to make it to the Sounds, we hadn’t sufficiently planned for Wellington, but the port control officer was helpful and told us where we could anchor for the night, a lovely place called Somes Island.

The next morning, we managed to get a slip at a marina and spent a few days in Wellington before getting another weather window during which we could cross the Cook Strait. We never did see the other boat again as they ended up days ahead of us in cruising the Sounds.

This actually worked out well in that we had a terrific time in Wellington, but it was also a good lesson in seeing just how much difference a bigger engine can make in a boat’s overall progress. Again, that other boat wasn’t much bigger than ours, but it had a lot more horsepower! They went from leaving well after we did to being many miles ahead of us in less than 24 hours, miles that made a difference in our outcomes. Below, a map which shows our initial plan (the green line), actually achieved by the other boat, and our surprise second plan (the yellow line) where we ended up in Wellington.

The moral of this story: Never figure you know what another boat is capable of and assume you’ll have safety in numbers by leaving when they do. If they’re out of radio range (which pretty much happens when a boat moves out of the line of sight), they won’t be coming to your aid if something goes wrong. In our experience, boats often separate very quickly once they head out on a passage.

This brings me back to the issue I mentioned earlier, how the actions of one boat can affect others. This isn’t at all the fault of the “instigating” boat but instead is the fault of those who fall under the spell of the Sheep Mentality. The story below, which also happened in 2016, is a perfect example of how this thinking can lead people to make terrible decisions.

It was late in the season in New Zealand and weather windows to the tropics had been particularly scarce that year. Cruisers had gotten increasingly desperate as time marched on, and many ended up making rough passages to the tropics. It was now well into winter, but thankfully this was the year Rich and I had traveled out of the country and managed to extend our visas. Between our extra visa time and the particularly mild and lovely winter in Opua, we were in no hurry to leave. We couldn’t, however, say the same for the remaining cruisers in Opua and Whangarei, who were incredibly anxious (to put it mildly) to get to the tropics. We’d been watching Marine Traffic and YIT (Yachts in Transit) to see who would be leaving during various times.

There was one weather window that wasn’t very good at all. Any boat leaving New Zealand would have a couple of days of beating into northerly winds, but if they could make it to a certain latitude within that time, they could get above a nasty weather system due to hit the area and have nice weather in which to continue on to Fiji or Tonga. We knew one boat in Whangarei was planning to take the window, a big yacht who likely had a good and powerful engine with which he could power into opposing wind and seas.

After this boat announced its intentions, another boat popped up and opted to take the same window. This boat was a fair amount smaller and while I’m no expert, I knew there was no way this sort of boat could have the engine capacity or sail power to beat into the wind for two days and keep up the speed required to outrun the coming weather system. I also didn’t have to be a psychic to see what was going on: The smaller boat had fallen under the spell of “There’s another boat going” and wasn’t thinking clearly enough to realize that the bigger boat would beat them by a long shot.

Monitoring Marine Traffic, we watched the inevitable scenario play out over the following days. Both boats left as planned, but the bigger boat used its engine to make good headway in spite of beating into northerly winds gusting to 20 knots. Around 48 hours later, that boat barely managed to squeak above the weather system that came in just below it, relieved and very happy as they reported on YIT that they’d made it and now had good weather to continue to the tropics.

The second boat, naturally, did not even come close to making it and now, after two days of beating into northerly winds, was caught in a nasty low which they’d have to ride out. The boat they felt they’d “be with” (who probably wasn’t even aware of their existence) would be checked in at their destination, enjoying happy hour drinks in a tropical bar while the second boat would still be in the middle of a long and difficult passage.

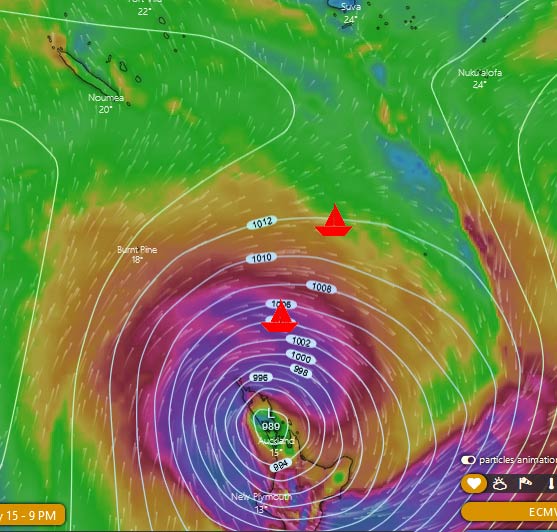

Below, an image of a typical weather system hitting New Zealand from the northwest, reminiscent of the one we watched in 2016. We’ve added icons of the approximate positions of the two boats when the system like this hit, two boats that left at the same time but had far different passages.

Rich and I have seen this scenario happen repeatedly, and the lesson here is that no matter how many boats are leaving, sail as though you’re on your own because you probably will be. Don’t fall under the illusion of safety in numbers! There are so many factors that create rapid distance between boats leaving a place, and it’s not just engine power or boat size. Just a few miles of distance can completely change the current and even the strength of the wind! And one thing we’ve seen over and over is boats forgetting just how much opposing conditions can slow them down. They count on a 5-knot average only to discover they can only make about 1 or 2 knots, especially if they’re beating into rough water.

The Sheep Mentality can work differently depending on the situation and the number of boats involved. In the type of scenario I mentioned above, the leading boat isn’t concerned with, or even aware of, the boats following their lead. But in the first example I mentioned, the “gathering of the herd,” a sort of magical thinking sets in: if enough boats go, then somehow everything will be OK. The fates might conspire to wreak havoc with one or two boats, but surely they wouldn’t dare do such a thing to a group!

There’s actually no truth to this, but magical thinking tells us that it’s so. Thus, the more boats that go, the safer it will be for everyone because Nature would never take out an entire group. There’s also the subconscious idea that some boats must be fated to have a good passage; thus everyone around them can benefit. I don’t think people are even aware that they might have such beliefs, but it becomes evident when, during times of what we on Legacy call “weather hysteria,” a group decides to take a weather window and on finding that Rich and I are opting out, actually get offended and upset—why is their window not good enough for us? It’s like we’ve personally insulted them.

My feeling isn’t that they so much worry about us getting left behind; it’s that our decision to pass on a window throws doubt on their decision to leave, and that makes them uncomfortable and thus pretty unhappy with us.

This is so pervasive that Rich and I sometimes resort to telling white lies about some broken part we need to fix before we can leave (actually this is often true as things have a habit of breaking at the last minute). This doesn’t always deter the people pressuring us in that they sometimes offer to lend us a replacement part (often not quite right but maybe it would work) or the name of a person who can fix it quickly even if we’ve already ordered replacements and are on top of taking care of it! With safety in numbers thinking, each and every boat contributes to the magical umbrella of protection, and each boat who opts out takes away a piece of that umbrella. Again, I don’t think people are consciously aware that they’re thinking this way, but it becomes evident with how weird and pushy some people can get when it comes to these passage window decisions.

One particularly annoying example of this happened during that difficult winter season in 2016 when we were sitting in Opua waiting for a weather window to get to New Caledonia. It was now July and there were still a few boats waiting to make the jump. A window of sorts had arrived and a handful of boats opted to take it. Meanwhile, we saw a window that might be better a few days later; so while people were in the customs office checking out, we went there to make a tentative appointment to check out the following week.

A man checking out asked if we were leaving that day, too, and we said no, we were waiting until the next weekend. He proceeded to give us a real dressing down, citing the latest report from Gulf Harbour Radio and pretty much telling us we were being stupid, that their passage would be great while our window was going to get delayed. It was all given with that stern undertone of scolding a naughty child. It didn’t help that the customs agent stared at us as though she agreed with him that we being negligent. We didn’t argue (not having listened to the latest report from Gulf Harbour Radio), but by the we got back to our boat to recheck the weather, I was in tears. I felt like we’d been made to look like fools in front of the customs agents, people who’s job it is to make sure cruisers don’t overstay their welcome.

Rich checked the weather again and saw that while our possible window wasn’t looking good; the one today still looked bad and wasn’t one we’d ever consider. The group of boats departed that afternoon as planned, but the next morning we heard from a friend that those cruisers were in for some bad weather. This prompted us to tune into Gulf Harbour Radio just in time to hear David advising this group they were going to go through a pretty bad trough. He added, “You guys knew this was going to happen (as in don’t complain to me), and now you need to be ready for it. Tie everything down, don’t go out on deck as we’ve had two deaths already this season, and know that tomorrow is just going to suck!”

I was flabbergasted! Did the stern lecturer from yesterday not know about this? I took the liberty of looking at his YIT (Yachts in Transit) post from the day before he left. He expressed concern about the daunting weather and wave forecast and felt “unsure of what to do.” This was followed by his post the day he left saying they were “being brave” and heading out. So this guy who was telling us how great their window was, that David was telling them to head out now, and how stupid we were being to wait was basically telling us bald-faced lies. The question is why? What in god’s name reason could this man have had for trying to convince us we needed to leave when he knew it was bad window.

I believe I may know some possible reasons: hope that another boat leaving might somehow bring some luck to the group, being unable to conceive of the idea that it’s better to remain in Opua than get your butt kicked on a passage, or maybe just that misery loves company. In any case, I was pretty taken aback by all of this. And I have to admit to some schadenfreude upon hearing they hit some bad northerlies even before the nasty trough clobbered them. As they say, karma’s a bitch!

As for us, our hoped-for window did fall apart, but we didn’t mind. We ended up waiting nearly another month for an appropriate window, but having decided to skip Vanuatu that year we were in no hurry to leave and frankly were enjoying taking a break and Opua’s surprisingly pleasant weather that winter. When we did leave for New Caledonia in August, we had one of the best passages we’ve ever experienced. In this case, it was all’s well that ends well.

In all, our advice here is to beware of the Sheep Mentality. Don’t assume you’ll have safety in numbers because that’s an illusion. Don’t assume your boat will perform as others do. Don’t take people’s word for things: double check the weather situation for yourself. Don’t let people pressure you into taking a passage that makes you uncomfortable as they may well not have your best interest at heart. Always act as though you will be on your own out there and plan accordingly; don’t for a minute assume that by following another boat that you are traveling in tandem with them. Unless you’re actually friends with that boat and have a schedule to keep in touch, they will be worried about their own voyage, not yours.

Beware the Sheep Mentality; it might be one of the greatest dangers out here.–Cyndi

Other parts in the series:

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 1)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 2)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 3)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 4)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 5)

Real Cruising Danger #2: The Sheep Mentality (this post)