September 13, 2019

(Continued from Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters)

To those who ask us if we’re afraid of pirates, I say not in the areas we’re currently traveling, but there are some dangers from other people. (I must hasten to add that these dangers are not all-consuming and nowhere near the threats one encounters from “bad” people while living a normal land-life.)

Aside from bad anchoring practices (last post), here’s another hazard other boaters can present. This one hits home with me because I can be intuitive about potential trouble, potential that my partner might not pick up on. This has caused more than one disagreement between us over the years.

b. Dangerous People Who Appear Normal

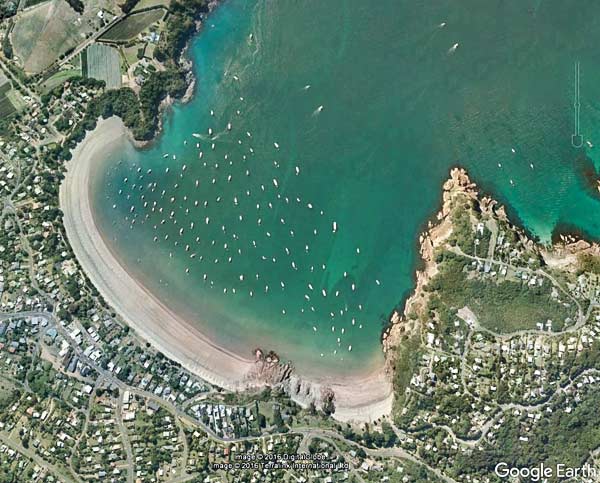

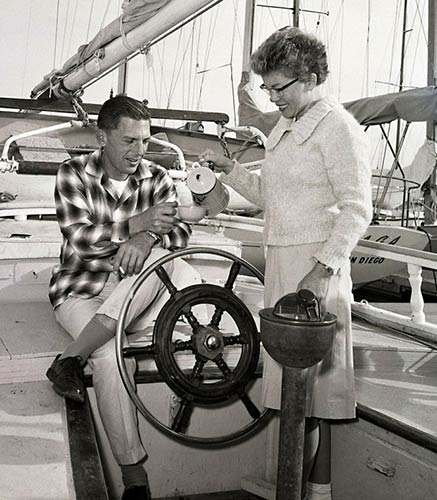

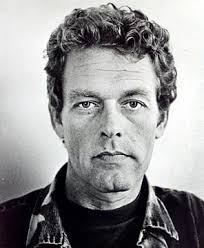

In 1974, Malcolm “Mac” Graham and Eleanor “Muff” Graham sailed their beautiful ketch, Sea Wind, from Hawaii to Palmyra Atoll. Also at Palmyra were Buck Walker and Stephanie Stearns, who’d arrived in a shabby, poorly-provisioned boat named Iola.

The following September, Sea Wind returned to Hawaii in the possession of Buck Walker and Stephanie Stearns. In spite of being repainted and renamed, the ketch was soon recognized by acquaintances of the Grahams, and Buck and Stephanie were arrested for its theft. The Grahams, meanwhile, had vanished. Buck and Stephanie’s story: the Grahams had gone fishing in their dinghy and never returned; so they simply helped themselves to their boat.

Eventually Muff Graham’s remains were discovered in the surf off Palmyra, along with a large metal container that had previously been weighted down and held those remains. Apparently King Neptune decided he didn’t like this particular “gift” and had tossed the container back onto the atoll, breaking it open. Buck Walker ended up being convicted of the murders of Mac and Muff Graham, while Stephanie Sterns was acquitted (although some believe she must have been an accomplice in the murders).

There’s both a book (written by Manson Family prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi) and a movie that depict this story, titled And The Sea Will Tell.

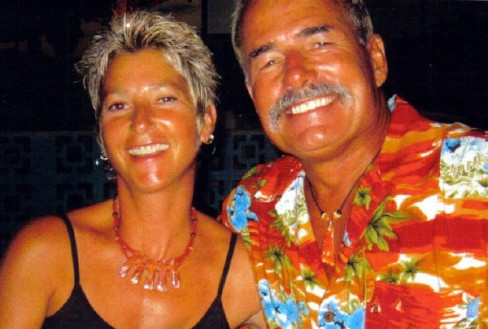

While things like this happen rarely, they do happen. Thomas and Jackie Hawks were another couple targeted for their boat.

In 2004, Thomas and Jackie Hawks were selling their boat and had received a full-price offer from a former “child actor,” Skyler Deleon. In truth, Skyler’s biggest gig was that he’d been an extra on a single episode of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers (a children’s TV show).

Getting a full-price offer plus another 15K for personal items (suspicious in itself) from a guy who’d merely been an extra should have aroused suspicion, especially since Thomas Hawks was a former parole officer and Skyer turned out to be an ex-con. But the Hawks were very anxious to sell their boat so they could move to Arizona and be near their new grandchild, plus they’d been charmed by Skyer’s pregnant wife and small baby. Unfortunately, they really let their guard down.

For the sea trial, Skyler showed up with two friends, one he claimed was his accountant. To make a long story short: The Hawks took the group out for the sea trial and ended up being tasered, bound, forced to sign a power of attorney granting their assets to the Skyler and his wife, then tossed overboard while tied to an anchor. After a long and difficult investigation, the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and sent to prison. Their motive: They wanted to live on the boat in Mexico and run fishing charters.

These are not nice stories, but they do serve as a reminder that evil can reside in ordinary-seeming people. This may seem like more of a problem for wealthy homeowners, people with real valuables and assets vs. the comparatively meager pickings on a yacht. But as cruisers we should remember that we, too, possess something others might see as extremely valuable: a means by which to escape and live freely.

For some who don’t know the ocean, they see us as having a home that floats, sails that gather a free source of propulsion, a sea that provides food for the price of a fishing pole and lures, and the answer to the wishful statement of, “Let’s go away and find a beach somewhere.” Those of us who actually cruise know this perception does not match reality, that the sea and wind would just as soon kill you, fish are not so easy to catch, and all beaches are owned by someone. Even if a boat opts not to use AIS (a tracking and identifying system), it’s still visible via binoculars and radar.

On the off chance that a yacht does manage to traipse through one country undetected, the next country officially visited will demand passports, paperwork and accountability for time and, as one young man found out, will not believe that it took the boat eight months to sail from, say, Mexico to Fiji. (The young man I referred to had actually spent months in French Polynesia without bothering to clear in and ended up in a lot of trouble for that in Fiji). Countries cooperate with each other far more than many people realize.

Perhaps more dangerous than psycho cruiser wannabes are the underfunded psycho cruisers who’ve procured a run-down boat (much like Stephanie and Buck Walker), believing at first in the easy dream before realizing they need something better equipped. That’s when they might start taking a look at boats they could never afford and fantasizing how those boats might look disguised with a different paint job. Most likely, this scenario would remain a fantasy, but given the opportunity, some people are capable of very bad things.

As for how often problems like this occur, I know that while sailboats are stolen every year, incidents where the owners are harmed are rare. (Note: I’m not talking about actual piracy here; just boat theft which is not the same as piracy.) Murder is more often a potential than something that actually happens, but it’s a potential I believe we should stay aware of, just as we do when living on land.

I think social-type cruisers can be especially vulnerable here as they don’t want to see the bad in anyone. It’s not the strangers they need to be afraid of; it’s perhaps their new “friends.” When I feel uncomfortable about a new acquaintance; I let Rich know. He’s come to realize I’m often right to be wary, even though it’s seldom put to the test as I try to get us away from people who make me nervous.

Occasionally I’ll share my wariness with another cruiser who will assure me a particular person is “harmless.” Personally I’ve found that people who’ve been declared harmless may be so to those making the statement, but not necessarily to everyone else. I’ve had more than one scary encounter with individuals I’d been assured were harmless.

Over time, I’ve learned to trust my gut over what people say. At the risk of sounding sexist, I think many women have honed (or been born with) good intuition and may be better at sensing trouble. But no matter what a person’s gender, if one person on the boat is more intuitive, it would pay for the other partner to at least take into consideration their discomfort.

Muff Graham had a terrible premonition about the cruise to Palmyra, which is known today because she shared her fear with family and friends before she and Mac left. She was so anxious she was prescribed anti-anxiety medication and even consulted a psychic for reassurance, but it turned out the psychic sensed trouble, too. She did not want to go on the trip, but Mac wasn’t deterred and they ended up going. Sadly, her premonition that she’d die a horrible death came true.

One thought I’ve had: if Muff was so nervous about something bad happening in Palmyra, she must have picked up on the danger surrounding psychopaths Buck Walker and Stephane Stearns. I’d bet money she asked Mac to leave and he refused, not wanting to change his plans based on an unsubstantiated “feeling.” He paid for that with his life.

The friends and families of cruisers often worry about pirates; but if care is taken in choosing sailing destinations, the danger of pirates is practically nonexistent. I’d worry most about the cruisers who are open, friendly, and looking for the best in everyone. These are wonderful qualities, but like a very friendly child or pet, you have to worry about them a little bit more.

One of the many advantages to cruising in this day and age is that it’s easier for those back home to keep track of, and in touch with, their cruising friends and loved ones. And a very good security precaution for friendly types is to have a more reserved, intuitive partner. You just have to be willing to listen to that partner even when they’re telling you something you don’t want to hear.

Trouble like Mac and Muff encountered is extremely rare but does happen. Food for thought. –Cyndi

Other posts in the series:

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 1)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 2) (this post)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 3)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 4)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 5)

Real Cruising Danger #2: The Sheep Mentality