September 3, 2019

People always ask us if we’ve felt frightened by pirates or storms, but over the years the greatest danger we’ve experienced has been brought about by other boaters. How do they threaten thee? Let me count the ways:

a. Bad Anchoring Practices

Before I go into this, I’ll first describe the basic method for anchoring a boat:

Step 1. Choose a suitable spot and determine the depth, then use this number to calculate how much scope (length of chain or line from bow to anchor) you’ll need. A ratio of 7:1 scope to depth is the rule of thumb, but that’s usually a bit extreme for mild conditions. Often 6:1 or even 5:1 will suffice. Check to make sure the boat will be able to swing freely in all directions as squalls and surprise wind changes can and do happen.

Step 2. Having stopped the boat, drop the anchor until it hits bottom, then slowly back the boat away from the anchor, paying the chain out as you go until you reach the amount you’ve determined you’ll need. Lock the chain or line down; then continue to back on it until the anchor is set and the line is taut. Now increase the throttle some, pulling back hard to make sure the anchor is really dug in. Take a look around and make sure you’re a good distance (approximately double the amount of scope) from any neighboring boats. Set an anchor alarm or check periodically to make sure you’re not dragging. Note: Never assume neighboring boats will swing exactly the same way yours will—windage, underwater shape and current can create big differences in the way boats hang.

Step 3. It should go without saying, if the line does not stay taut as you pull on it or you end up too close to another boat, you will have to bring the anchor up and try again (and again) until the anchor holds. If it won’t, you’ll have to move to another spot.

That’s it in a nutshell, simple and straightforward, yet many boaters simply refuse to do this properly, either out of laziness, ineptness, selfishness or its opposite: being more worried about queuing than basic safety. Over the years we’ve seen all these scenarios and end result is the same: a hazard for everyone around them.

I must hasten to add to this list misjudgment, because nearly all of us are guilty of this at times. We go into an anchorage, locate a spot, go through the process of setting the anchor and then look to see how the boat’s laying in relation to the boats closest to us. Sometimes, alas, we’re just too close to another boat. With that, we pick up, relocate and try again, apologizing if the neighbor happens to be up on deck looking worried.

This is what a good boater does, but some people are stubborn: they feel entitled to be in the spot they chose, don’t feel like anchoring again, and if you don’t like it, that’s your problem—get the stick out of your ass. We’ve had a few yelling matches with these people over the years, usually getting them to move because Rich can really holler, but a few times we’ve actually had to pick up and move ourselves, all the while hoping karma would do its thing to the interlopers.

Another reason for bad anchoring is the queuing thing, which tends to be cultural. There are areas of the world where, come summer vacation, there are too many boats and too few spots to anchor. Thus, there’s an unspoken understanding that everyone will anchor too close together, reasoning that all boats will swing the same way and when they don’t, well, put out some fenders.

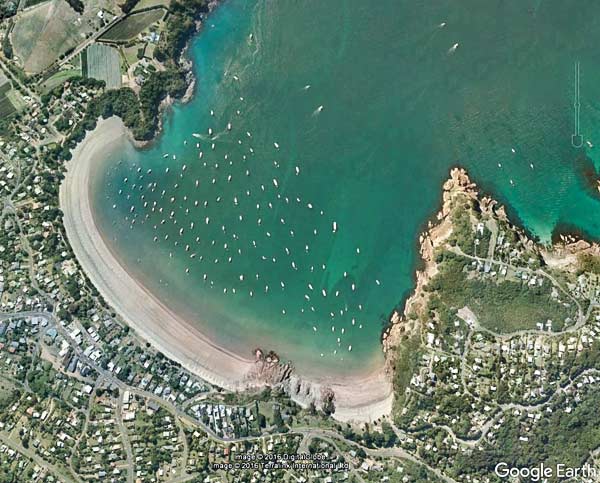

New Zealand is one of these areas, and newly-arrived foreign cruisers can be in for quite a surprise if they go cruising during peak summer season. It certainly was a surprise for us! I can’t tell you how incredulous we’d feel anchored in an empty bay, hearing noise and looking outside to see a boat anchoring right on top of us. “Oh my god, what are you doing?!,” we’d yell. For us, it’s like being comfortably seated at a restaurant and having another couple plop themselves down at our table—it simply isn’t done. If the restaurant is empty, you find your own table, and if it’s busy, new arrivals have to wait. If the restaurant is fully booked, one has no choice but to go elsewhere. Kiwis certainly follow this protocol at restaurants, but when it comes to anchoring, they are pretty much joining you at your table in an effort to make room for the anticipated lunch crowd.

Thus, when we’ve protested over a boat anchoring way too close, we’ve heard, “There will be 50 boats in this bay by the end of the day!” as they angrily and begrudgingly move. In our view: there will not be 50 boats because there’s not room for 50 boats, and we have no obligation whatsoever to make room. Safety, for us, trumps empathy. (Interesting note: Since we don’t cruise in New Zealand at the height of vacation season, none of these anticipated crowds has ever shown up after these altercations. The queuing thing is just so ingrained that some people think they have queue all the time.)

I will say there are two solutions for overcrowded areas in places where there’s no alternative anchorage. In Hiva Oa in the Marquesas where many cruisers make landfall, it’s protocol for all boats to use a bow and stern anchor in the bay, and that works well to fit nearly everyone in.

In other check-in (or popular areas) without big marinas (Neiafu, Efate, Savusavu, Musket Cove, etc.) the countries have installed mooring fields for their visiting yachts. These moorings do need to be maintained and aren’t free of charge, but they can usually fit everyone in. They also serve to prevent the incompetent anchorers from getting too close, although we’re occasionally shocked by some idiot who attempts to anchor amid moorings.

At Catalina Island off California, the most-used bays have double moorings installed where both the bow and stern of a boat are attached. This allows boats to be lined up closely in long rows so that many more people can visit during peak season. Since they are presided over by a harbor patrol and do cost money, there are those who lament their installation. But the population has grown and in this case, it’s appropriate to accommodate more people as long as they don’t overcrowd the island itself. It would be a shame to mar the beautiful anchorages in the Bay of Islands and Great Barrier Island with mooring floats, but if it’s that important that everyone get a spot, the powers that be might want to consider it.

There’s a final reason for incompetent anchoring, and that’s laziness. There are those who drop their anchor while their boat is still moving forward and consider it set well enough. Even worse are those who don’t bother to set the anchor at all. We had a Kiwi friend who told us of going to the Cavalli Islands and was tired after a long day; so he just dropped his anchor and didn’t set it. That night the wind shifted and came up strong, and he woke to find his boat rapidly dragging into the rocks. He barely managed to get the boat going in time to avoid them and was clearly shaken by the experience. We didn’t want to criticize him as he was traumatized enough, but how on earth can a person be “too tired” to take such an essential safety precaution as setting their anchor?

I will say now that in spite of all my jumping up and down about bad anchoring, I have to allow that in real life, cruisers often push the envelope, and that much of the time in a busy anchorage we’re in a gray area as far as being the correct distance from each other. By “gray” I mean a bit too close, but not too far out of line. When this happens, we might take in some scope to allow more room for another boat. When just 10 or 15 feet can make a difference, the bay is well protected and there’s nothing nasty in the forecast, we’ll do this and at times people do it for us. It just depends on the circumstances.

And admittedly there are those times someone is too close, yet not way too close, and we just don’t feel like getting into it by asking them to move. We paid dearly for this once and ended up in what I’d call our most dangerous moment in our 45,000 miles of blue-water cruising. It happened in the anchorage off Pangaimotu Island in Tonga. This anchorage is reasonably well protected in prevailing winds, but otherwise pretty open as it’s off a small island. We had a good spot in the area closest to the beach. Spread out from the island we had a crowd, but the spacing was pretty good. A larger boat came in and anchored outside of us but a bit too close. We thought about going over and complaining but decided well, it’s pretty busy, we’ll let it go.

Things were fine until that night. Rich was on our radio net when the squall hit, instantly windy, rainy, and gusting hard into the anchorage. The wind had turned and was blowing 25 knots, all the boats now facing out with the island behind us. It was pouring rain, and the chop rapidly getting more impressive. I noticed the motion of our boat felt odd but chalked it up to the current. I went out to take a look and was shocked to see the boat that had anchored outside us was now way too close.

At this point, things got frantic. Rich grabbed our Fire Vulcan flashlight and flashed it at the boat, yelling that he was dragging down on us. That wasn’t the only problem; we realized the strange motion was us touching the bottom as the chop was bouncing us up and down quite a bit. Thankfully, it was a soft muddy sand bottom, but this was still not good.

At this point, we could have fixed our situation until the squall passed by taking in a few feet of scope, which Rich went forward and did, but now we were just feet from the other boat. The captain was in his cockpit but determinedly ignoring Rich has he flashed our light and yelled. Obviously, the neighbor had no intention of doing anything to help the situation, and there was no getting around it; we needed to move and do so immediately!

By now, constant lightning had started and we were hearing the rumbling of thunder (thankfully not quite coinciding with the lightening). It was dark but the flashes would light up the world around us for a moment, almost like daylight. Barely dressed, I ran up through pouring rain to the bow to get the anchor up. Rich motored up on it, and the flashing light provided some assistance as I would point towards the direction the chain was going all the while hanging on with one hand. We got the anchor up, which Rich later told me it took full-throttle to do.

The anchor now up, we headed to a new spot to re-anchor. The sky kept lighting up all around us, but I couldn’t watch to see whether it was bolt or sheet lightning as I needed to keep an eye on what I was doing and occasionally look back to Rich, trying to yell loud enough so he could hear me. We anchored again, but as we backed to set it found were headed right back at the other boat, again too close. We would have to move again to a completely different spot.

Meanwhile the wind had shifted slightly, putting our problem boat too close to a neighbor who’d been near us, a person who’d had been there first and had anchored properly. The problem boat was now dragging down on this innocent boater and had the gall to flash his own flashlight at him as though implying that he was at fault and like us, should pull anchor and move.

We anchored once again, but in the yellow of our deck light, I missed a round of yellow chain markers and put out 30 feet too much chain. I quickly took some in, but we were now too close to shore. So in the the midst of all the lightning and increasingly rumbling thunder, we would need to anchor again for a yet a third time.

By now we were both soaked, me by both rain and seawater splashing over our bow. I yelled to Rich that we should anchor near a boat at the outside edge of the anchorage. We knew he was holding well and away from everyone. Rich could hardly see with his wet glasses and used the radar and flashlight to locate this boat. We pulled up behind it and dropped the anchor, and now I was praying it would hold as it became increasingly dangerous for us to be outside. Thankfully this time the anchor set and held.

Rich came up and put our Anchor Buddy (a heavy weight that helps hold the anchor chain down) on and we set the snubber. We headed back to the cockpit and got a big clap of thunder along with a flash of lightning. Rich urgently told me to get below while he stayed outside to turn off the engine. It was a relief when we were both in the boat, holding well in deeper water. Frankly I knew all along I could die out there as standing on a boat in a thunderstorm is extremely risky, but at that point I put my life in the hands of fate and totally focused on the task at hand.

Back inside the boat, drying off, we now had the luxury of realizing the danger we’d been in and were seething mad at the neighbor who’d anchored too close and put us in a life-threatening situation. I’m sure the other boat he dragged down on wasn’t too happy with him, either. But then again, we had earlier opted to let this go and this is what happened. So this scenario, right here, is the reason we protest when people who get too close. Surprise squalls do happen, especially in the tropics; and boats have to be prepared to be turned in all directions.

Over the years we’ve heard Gulf Harbour Radio, who provide weather forecasts for cruising boats, take some guff over just these sort of situations that have gotten people into trouble—why didn’t they warn everyone?! Because they can’t predict squalls, that’s why! It doesn’t happen frequently, but it does happen often enough that one has to act as though it will happen. One slip-up can mean (and has meant) the end of a boat.

There is one more scenario, the Sheep Mentality, that I’ll be talking about, but since it overlaps with this one, I’ll mention this story…

Every year the 100 plus boats that participate in the Puddle Jump are treated to a celebration party in Tahiti. Naturally some of us are at the back of the pack and can’t make the party, but there are plenty of people at the front end who attend. In 2012 this party was held at a particular beach on Moorea Island. The anchorage here, between the beach and a reef outside of it, holds (as memory serves) about 25 boats. But for this party, about 60 boats packed themselves in. Most of these people knew better (and we know at least one boat who saw the danger and opted to leave, missing out on festivities they had very much looked forward to), but in this case an authority figure, the organizers of the Puddle Jump, said it was OK to put too many boats in there.

That night after the big party, a squall came up bringing 40+ knot winds. Chaos ensued while boats drug and bumped in the night. There was damage to some of the boats, and it’s amazing that no one ended up on the reef. It was certainly talked about the rest of the season as those who attended had quite a story to tell, and the Puddle Jump was nicknamed the “Puddle Bump,” that night. Cute, but I have to say whoever organized that party should be taken to task over encouraging such unsafe behavior. I hope that they have since either chosen a better spot for their party or provide transportation from a safer anchorage.

Note: I’ve looked over a couple of the articles about that party in Latitude 38, but I didn’t see any mention of the disaster that (I believe) they were responsible for that night.

I was going to make the danger of Other Boaters into one post, but this topic is so big I’m going to break it up. Stay tuned for “Let me count the ways: b, c, ?” -Cyndi

Other posts in the series:

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 1) (this post)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 2)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 3)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 4)

Real Cruising Danger #1: Other Boaters (Part 5)

Real Cruising Danger #2: The Sheep Mentality