November 21 – 29, 2013

One of the disadvantages of leaving the tropics in windless weather is it can be rather hot, but with the accompanying calm seas, we can open the overhead hatches to let some air come through the boat as we motor along at 5 to 6 knots. It’s not ideal, but we prefer these conditions to getting knocked around by rough wind and sea conditions.

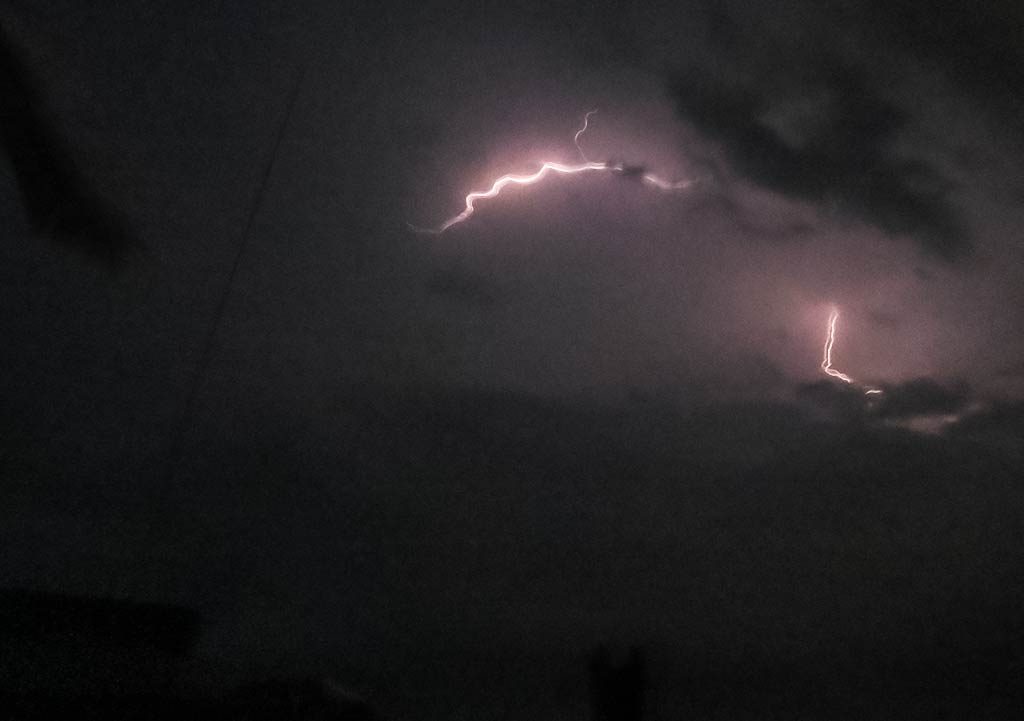

There was one bit of foreboding, and that was that the sea, usually glassy in these conditions, was washing-machine bumpy, a sign of squall activity about even if we couldn’t see it. I was on my night watch when I saw the first flashes of lightning. I went outside and could see bolts streaking across the clouds behind us and to the east. Thankfully it never got too close to us, but it did seem to follow us for awhile.

The next day was once again hot and still. While there were some squalls during the night, the only light came from the moon and the bioluminescence in the water.

The third day, in spite of some cloud cover, the warm and windless weather continued. These hot still days brought us beautiful red sunrises and sunsets.

It wasn’t until the dead of night that we started to get some weather drama. The air and sea continued to be calm, but the sky started to light up with flashes of bright light – lightning, and it was pretty dramatic! This is when having radar really helped as we could locate the system and see it was about 20 miles to the east of us.

Even though the system was pretty far away, it was bad enough that we decided to put more distance between us and it; so we turned and headed west for awhile. Still, the lightning was so bright that lying in bed I could see near-constant flashing light through the curtains over our ports. Too nervous to sleep, I got up and joined Rich in the cockpit to watch the show. Bolts of light streaked across the sky, but the scariest were the bolts we could see hitting the water in the distance. We were glad we had turned because this system crossed the route we’d been on!

As it was we weren’t hearing much thunder, but we did put our GPS, dongle and I Pad in the oven (which we hoped would serve as a Faraday cage). We took comfort in looking at the system on radar because it reassured us that it wasn’t as close as it looked (and it looked like it could practically be over us!).

We did eventually see another good-sized squall to the west, so we turned south again, threading the needle through both squalls. Finally the lightning became more distant, and I was able to sleep in spite of still seeing flashes of light through the ports. It was a relief there was no thunder with the flashing light, but it was also strangely creepy.

The next morning brought more warm, light air and a sky made white by cloud cover. We crossed the Tropic of Cancer, and somehow I thought this would magically bring cooler weather, but it didn’t and we opened our hatches once again. The next day was pretty much the same. At least the lightning hadn’t come back.

Our fifth day brought a warm front, which was humid and muggy with a bit of rain. We were still motoring but now getting anxious for some wind as we couldn’t quite make it to New Zealand on our fuel alone. That night on my watch, I got my wish when the temperature suddenly dipped and the wind picked up from the northeast, just enough to sail. I put out the headsail, trimmed the sails, and turned off the engine. We were now were gliding through the water at 5-6 knots on a beam reach.

They say the happiest days in a sailor’s life are they day they buy the boat, and the day they sell it. But I would also include the moment when, after days of motoring, the wind comes up just enough to fill in the sails and propel the boat through still-calm water on a beam or broad reach. The sound of the droning engine is replaced by that of water swishing and gurgling as the boat glides through it, while nagging worries about fuel consumption abate. It’s truly a joyful feeling!

The next morning was still warm, yet gray and rainy. A trough went over us, bringing for a time unpleasant gusting winds and boisterous seas. But it passed, and once again we were moving along again in that magical combination of calm seas and a steady wind just behind the beam.

One of the things that can make a passage really nice, when the weather and seas are behaving, is the gift of free time. Part of the cruising dream generally involves having time to pursue one’s interests: the reading, writing, hobbies, or just sitting and thinking. It can be surprisingly hard to find time for this sort of thing during the travel-intensive (or even normal day-to-day living) times of cruising, but long passages can give us the feeling of having spare time, to spend as we wish, when the conditions are nice.

Unfortunately, nice conditions seldom last an entire passage. The spell gets broken when the wind picks up too much, or the sea gets rough. Sadly, things also take a downturn if the wind merely moves a few degrees and gets ahead of the beam. Today was that day. The conditions didn’t really change: the seas were a tad bumpy and the wind about 16 knots, but the wind went more south and ahead of the beam. It’s amazing how this changes everything. The boat heels more and the constant pull of the g-forces becomes so draining. Doing even the simplest task takes effort, and difficult tasks become near impossible. And naturally the mood onboard sours.

So far this had been one of our best passages, even when the engine was running constantly. But now everything was difficult and uncomfortable. Things got worse as we started to pass through squalls. The wind would gust as high as 25 knots, and the seas started knocking the boat around. I had plans for our Thanksgiving meal, but now it was too rough to make the steak dinner (no, we don’t do turkey on the boat) or even put champagne in the fridge. I did somehow manage to make green chicken curry so the special meal wasn’t a total loss.

Our final day brought southwest winds at about 16 knots, which meant we were going to weather. Going into this sort of wind, while best avoided, usually isn’t the end of the world. But in this case the sea state was pretty rough, making the sort of conditions that can suck the will to live right out of a person. It’s the sort of conditions where everything seems exhausting and difficult, and it takes a conscious effort for us not to snipe at each other. Even though we knew it was our final day; we were too miserable to take much comfort in that.

Later we were telling some Kiwi friends that we’d had to beat into 16 knots to get to New Zealand, and hearing our tone they said, “Sixty knots? That’s terrible!” We said, “No, not 60, it was sixteen; and it was horrible!” There was a moment of silence where I’m sure our friends were thinking we must be a bit daft, but it goes to show that there are many factors which either make an ocean passage pleasant or unbearable. Swell height is an obvious factor, but we find what matters far more is the period between swells. Wind speed is another obvious factor, but what’s more important is where that wind is blowing in relation to the boat. We’ve been more comfortable in 40 knots than we were in the 16 knots we had as we approached New Zealand.

Finally the conditions died down as we neared the coast. It was chilly but not that cold. When we headed outside to keep watch as we approached the shore, we wore hats and foul weather gear but also had bare feet.

In a remarkably exact repeat of our arrival the previous year, we arrived on a dark, moonless night around 2am. This time, though, we could make out the shapes of islands and knew what we were seeing. In the Bay of Islands, the wind had died off completely, and we could see the lights of Kerikeri reflected in the clouds above it, and the lights of Paihia along the shore. We soon spotted the customs dock and were relieved to see there was plenty of room. We got tied up as easily as one can expect while exhausted, in the dead of night.

As we motored in, we both felt pretty beaten up by the day and rather numb emotionally, but we had started to feel happy to be back on spotting familiar things. After we docked and turned off the engine, I heard a Kiwi’s shrill cry in the hills, a distinctly New Zealand sound, and it felt good to be back.

After doing some cleanup and taking showers, it was time to celebrate with some champagne. Yes, we’re tired after arriving but also excited, and it’s nice to sit up and let the arrival-excitment adrenaline dissipate while enjoying a bottle of wine or champagne. We knew there would be more hurdles to clear in the morning: going through customs and immigration, arranging a slip in the marina, then actually moving to that slip during slack tide. But at least we’d made it here and the big passage was behind us. Happy day!

Final Note: In going through our photos after we arrived, we came across this one (below) showing a line of light in our cockpit. Rich thought it was a reflection from the antenna on our stern rail, but I’m not convinced as the light appears in front of our barbecue grill. Frankly I don’t know what it is, but it looks like it could be a streamer.*

I assumed we were too far away from the system to get hit by lightning, but if that’s a streamer in the photo, we were apparently close enough, and thus very lucky this streamer did not connect with a leader. In any case, I find this photo very unnerving. –Cyndi

*Streamers are positively charged “branches” of electrical energy which reach up from objects on the ground in response to leaders generated in the clouds. When one of these streamers connects with a leader, it’s a lightning strike.